Was your ancestor a butternut? Blue tail fly? Sesesh?

Phrases or words unique to local or regional language are called colloquialisms. Also known as slang or vernacular speech, phrases like ax to grind, dead as a doornail, madder than an old wet hen, and just fell off the turnip truck are examples of older colloquialisms and jargon still in widespread use.

Many colorful ones can be traced back to documents found at the State Library and Archives from the Civil War era.

We've included a few examples below, which haven't been edited for spelling, punctuation or grammar. So, skedaddle on and enjoy these Civil War period colloquialisms.

A to izzard. Completely; thoroughly

“I was always a straight out Union man from A to izzard.” From the deposition of Wyatt Jeans in a court case styled Henry Wagoner v. Hannah Woolsey, admr. of Gilbert Woolsey (1869), Greene County. Hannah was suing a former Confederate soldier for her husband’s death at Andersonville Prison. (Tennessee State Supreme Court Records)

|

| Collection of D-guard Bowie knives, circa 1860s, Looking Back: The Civil War in Tennessee Collection. |

Arkansas toothpick. A heavy dagger, similar to Bowie knife, used by both sides in the Civil War. Again from a court case: Alexander Winder “unlawfully did carry under his clothes, or concealed about his person a certain large and dangerous Knife commonly called an Arkansas toothpick…" From State v. Alexander Winder (1867), Monroe County. (Tennessee State Supreme Court Records)

Blue devil; blue tail fly; blue belly, etc. In Confederate jargon, blue was derogatory as it was the color of Union uniforms.

Consider this citation from the Nannie E. Haskins Diary from July 14, 1864: “Guerrillas are all over the country, there are a thousand between Louisville & Henderson firing into boats and getting horses from the Southern army. The Journal [newspaper] has been rather gloomy for several days, old Prentice has the blue devils.” “Old Prentice” was Brig. Gen. Luther Prentice Bradley, a brigade commander in the Army of the Cumberland.

Or this one, from the same diary, from March 2, 1863:“…I am rattling on too fast if our men get to Fort D. probably they will not come here, Oh but if they do what a pleasure it will be to have the ‘bonnie greys’ to look at instead of the ‘Blue tail flys’ I am perfectly disgusted with the color blue, I never want to see any thing blue again.”

This entry from the Lucy Virginia French War Journal from July 17, 1862 notes: “His information was that a victory [1st Battle of Murfreesboro] had been gained sure enough‒that a company of men had just gone on to town with Gen. Crittenden & his staff as prisoners‒that more were coming‒etc. And in a short time 13 wagons filled with the blue bellies, (as the boys call them.) came along. Squads were coming in all night with horses, prisoners etc.”

Bushwhackers. Bands of Union or Rebel partisans who raided towns and roamed the countryside plundering homes and businesses. Most were ruffians, murderers, thieves, and deserters. Usually they were locals, giving them the advantage of knowing the terrain.

|

| “Guerrillas destroying a Railroad-Train near Nashville” in Annals of the Army of the Cumberland by John Fitch, 1863, Library Collection. |

From the Lucy Virginia French War Journal, dated July 26, 1863: “Scenes enacted here [Grundy County] beggar description. Early in the morning the sack of the place began. But a few of the ‘bushwhackers’ were in‒the mountain people came in crowds and with vehickles of all sorts and carried off everything they could from both hotel and cottages…. They were emptying Mr. Cockrill’s house as we went to the schoolhouse, and two rough fellows were in our room playing the melodeon…. the scenes we witnessed are indescribable. Gaunt, ill-looking men and slatternly, rough barefooted women stalking and racing to and fro, eager as famished wolves for prey, hauling out furniture—tearing up matting and carpets….”

Butternut. Common slang for a Confederate soldier. The homemade dye used to color cloth when imported gray fabric became scarce. The dye was made from the husks, leaves, bark, branches and/or roots of butternut and walnut trees.

“They (the Yanks) came in once and sent one of their men on a head dressed as a butter nut of course he was thought to be one of our men…. That was the last we heard of the butter nut except that he proved to be a deserter from the Southern Army and a Yankee spy.” (Again from Nannie E. Haskins Diary, dated February 16, 1863)

Common as pigs tracks. Trashy; lowbrow; not unique

Commenting on Lincoln’s home in Springfield, Illinois, Lucy Virginia French wrote, “I may add that Mollie in one of her letters said that Ella Chew’s father had once resided in Springfield [Illinois] and knew the Lincolns—Ella said they were ‘as common as pig-tracks and as poor as Job’s turkey.’” (Lucy Virginia French War Journal, 7 October 1862)

Contraband. Runaway slaves who fled to Union lines. Typically, contraband camps were hastily constructed communities located near Union forces. Many of the ex-slaves joined the United States Colored Troops (USCT) or labored for the Union war effort. Often they were paid wages and given the opportunity to attend school.

|

| “Impressing the Contrabands at Church in Nashville” in Annals of the Army of the Cumberland by John Fitch, 1863, Library Collection. |

“There is a contraband camp [near McMinnville?] where she says poor wretches literally freeze to death by dozens during this severe weather—they have no clothes scarcely—bedding, shelter, and food the same, while their friends the Yankees curse and abuse them for everything low and vile and no account.” (Lucy Virginia French War Journal, 24 January 1865)

Durance vile. In jail; incarcerated

Interned at Johnson’s Island, Ohio, Capt. Charles E. Kennon signed a fellow officer’s autograph book, “Your friend in ‘durance vile,’ Captured near Franklin, Tenn., Dec. 17, 1864.” (A. S. Kierolf autograph book)

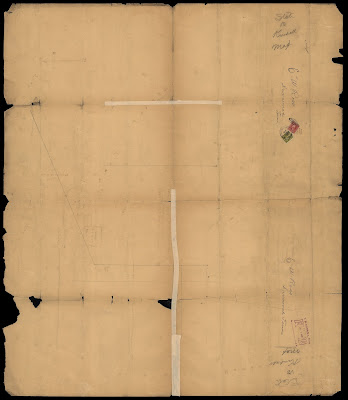

|

| “Plan of the Military Prison Situated on the South side of Johnsons Island” in Scraps from the Prison Table, at Camp Chase and Johnson’s Island by Joseph Barbière, 1868, Library Collection. |

Dutch/Dutchman. A German-American soldier; Hessian

While imprisoned at Johnson’s Island, Ohio, Capt. G. W. Youngblood of Memphis signed a fellow officer’s autograph book, “Grabbed near Port Hudson, La., March 16, 1863, by a Dutchman with the ‘sweet German accent.’” (A. S. Kierolf autograph book)

Jayhawkers. Bands of thieving, sometimes murderous, pro-Union guerillas. Term originated in “Bleeding Kansas” but was still in use during the Civil War.

“[The rebels] came dashing in on their old poor horses, dirty clothed and all sorts of armes, they had no band at all not even a bugle, or a flag, to tell show to whom they belonged but their old dirty ‘grey’__ but ‘fight was in um’, and they ‘tuck’ the the ‘Feds’ with all their blue broad cloth and brass buttons. They stied with us until the 7the [sic] of September they left and the Jay hawkers came from Fort Donelson on a thieving expedition….” (Nannie E. Haskins Diary, 16 February 1863)

Lincolnite. In Confederate-speak, any derisive compound word formed from the U.S. President’s name. A person with Union sympathies

“We are now in Yankee Land--as Grandma Lyon mentioned today. Why dear she said, I havent shaken hands with you since we all got into Lincolndom!” (Lucy Virginia French War Journal, 2 March 1862)

Mary Minerva Rutlege wrote: “The Lincolnites have been doing some mischief over on Clinch the night that I came up they set fire to John Lacheys barn and burned up some fine horses and about three thousand dollars worth of other things….” (Mary Minerva Rutledge to Dear Sister, 9 October 1862. Rutledge Family Papers)

Look like boiled cracklings. Worn; weary; exhausted

A letter from Amanda C. Lillard to Newton J. Lillard from May 23, 1861 stated: “I was over at Decatur yesterday found all the people well as common. But very loansum. The girls looks like boiled cracklings…. Poor girls what boys there are left here the girls are quareling which will have them for their beau.” (Lillard Family Papers.)

Making a belly bounce. To do harm [to another person]

“Adam Wagner said let him come [at me], I’ll make his old belly bounce.” read a line from the deposition of Hannah Woolsey, daughter of Gilbert Woolsey, in which she describes Confederate outlaws coming to kill her father on first sight. The family was suing the wartime ruffians for Gilbert Woolsey’s death at Andersonville Prison. (Henry Wagoner v. Hannah Woolsey, admr. of Gilbert Woolsey (1869), Greene County. Tennessee State Supreme Court Records)

Northern Bastille. A Union prisoner of war camp

“….to day just one year ago this terrible disaster [fall of Fort Donelson] took place; and my dear brother was among the number, who was to be sent and incarcerated in a Northern bastile‒where he languished and‒died.” (Nannie E. Haskins diary, 16 February 1863)

Robertson County. Robertson County, Tennessee, distillers produced some of the most popular whiskeys in the world during the 19th century.

From the Union prison at Fort Warren, Boston Harbor, Nathaniel Cheairs of Bedford County wrote, “….tell your Ma to save me a little of my Robertson County—as I expect to be very dry.” (N. F. Cheairs to Beloved Daughter, 25 May 1862. Figuers Family Papers)

Secesh/Sesesh. A Rebel; secessionist

“The Secesh women were frantic with joy when Kirby Smith’s army arrived [in Lexington]—they even went to the absurd length of hugging and kissing the horses of the soldiers. This is what abolitionists think very strange, as the horses had riders upon them.” (Lucy Virginia French War Journal, 19 October 1862.)

Seeing the Elephant. To experience combat.

Writing amid thousands of soldiers, one Union soldier described marching from Corinth "expecting every moment to see the Elephant." (E. R. Porter to Father, 10 May 1862. Looking Back: Tennessee in the Civil War)

|

| Letter from E. R. Porter to his father, Corinth, Mississippi, 10 May 1862, Looking Back: The Civil War in Tennessee Collection. |

Six Months Men. Near war’s end President Lincoln issued a call for additional troops. One incentive was the opportunity to enlist for six months, hence the nickname.

Skedaddle. To hurry along or leave with haste; scurry; run

|

| ‘The “Grand Skedaddle” Of The Inhabitants From Charleston, S. C., When Threatened By An Attack From The Federal Troops,’ undated, Manuscripts Oversize Collection. |

“We retreated from Greenville on a run to Bull’s Gap which we commenced fortifying our position as impregnable. Before the Telegraph had given publicity to the news our impregnable position was evacuated and we are ‘Skedaddling’ for Cumberland Gap.” (From a Union soldier’s letter captured by Gen. James Longstreet’s men. 16 December 1863. Lillard Family Papers)

Sprightly [or merry] as a cricket. Lively, energetic

From the Betty Family Papers: “Josephine & children quite well. The latter growing fast and are as wild & sprightly as crickets.” (James F. Neill to Mrs. W. F. Betty, August 18, 1864.)

To learn more, we encourage you to visit the following links on our website...

- Tennessee Supreme Court Records: http://sos.tn.gov/products/tsla/tennessee-supreme-court-cases

- Looking Back: The Civil War in Tennessee: http://sos.tn.gov/tsla/looking-back-civil-war-tennessee

- Women in the Civil War TeVA Collection (Nannie Haskins Diary, Rachel Carter Craighead Memoir, and Lucy Virginia French Journal): http://share.tn.gov/tsla/TeVAsites/CWwomen/index.htm

- Civilian Life in the Civil War TeVA Collection (Mary Minerva Rutledge Correspondence): http://cdm15138.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/landingpage/collection/p15138coll1

- Civil War Military Records TeVA Collection (General Order No. 11): http://cdm15138.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p15138coll9/id/178/rec/4

The State Library and Archives is a division of the Tennessee Department of State and Tre Hargett, Secretary of State